promising voice; while glaring sideways at any unfortunate prefect standing next to her who she did not feel was contributing to the proceedings in the proper, earnest manner. Worship was always Christian in those days, of course.

Another teacher called Mr Lockhart, an Irishman, was another character. (Looking back on it, almost all our teachers fitted that description, in one way or another, in those days. . . Is it the same now, I wonder? I suppose so, human nature being one factor that has not changed since then.)

I have a persistent memory of Mr Lockhart, who taught English, mostly, then, in Room 7 (A28 on the modern plan, just around the corner front the hall); and who normally spent a great deal of his time denouncing his classes quite rightly, for the most part as 'wasters': standing up on the school platform still quite unchanged from those days to read out, for the benefit of the school, his favourite passage from the Bible, which he did on numerous occasions, so much so that the words are now fairly branded into my mind thank God, I now say. For the passage he invariably chose was from the Book of Proverbs, (Chapter 16, verse 16):

How much better than gold it is to gain wisdom; And to gain discernment is better than pure silver.

The Book of Job, chapter 28, verse 18: 'Wisdom's price is far above rubies' was also among this master's pet passages, which always, as you will notice, revolved around the same theme.

After Assembly, it was time for the first lesson; sauntering casually (as we prefects at least did, though the other pupils marched strictly in line, usually marshalled by us!) past the old Chemistry lab on the 1st Floor (now B18) where Miss Bunting, at that time the distinctly elderly (Head of Science Department, who had once, very memorably, blown herself, and a few other pupils in the front row of the benches up! As you will be relieved to know, the injuries received were not serious. Far worse a hazard, as I have often heard mentioned, were the liberal amounts of saliva with which she used to besprinkle those devotees of hers who were unfortunate enough to have to sit within close range.

Suffice it to say that French at that time was taught by two Scotsmen, Mr John Grieve and Mr Stephenson in rooms corresponding to that marked B08 and A21 and A22; and A27 the latter being designated, at that time, the 'Music Room'. It ran in tiers of seats, like an university lecture-hall, on a minor scale (pun, unintentional) and great was my fascination, at the age of 11, as I remember, on being introduced to the charms of the French language at that time, with 'r's' even more ferociously pronounced than is customary anywhere lower down than 'Bonnie Prince Charlie's' terrain, I am sure.

Other memories flood back: ghastly smells, as of bad eggs, coming from the next-door 'Stinks Room' otherwise known as 'Advanced Chemistry' laboratory (now A26); long lazy afternoons, sitting with so-pleasant Mrs Beattie, in the sunny quadrangles, or school garden, reading Chaucer (one of my most cherished memories: where else but in England could you do that?); school plays and concerts and our heady VIth Form discussion group, the Vitalis Society (Does it still meet?).

But time. . . if not space, has run out now. .

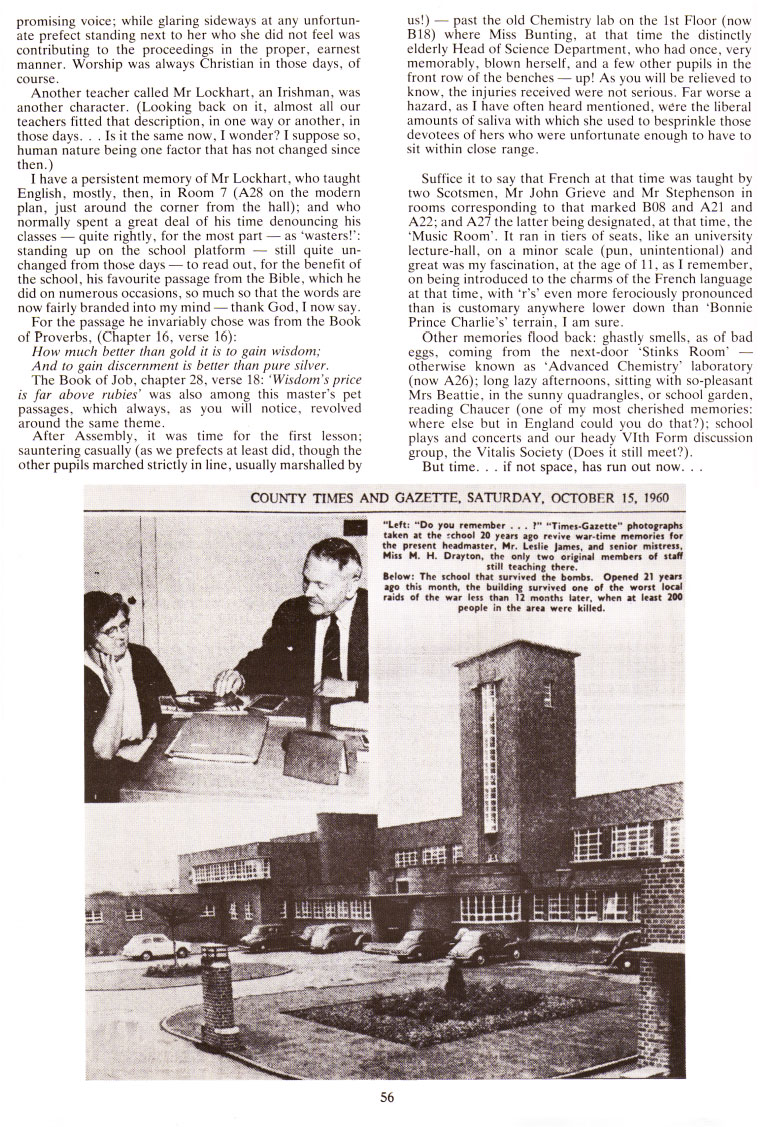

IMAGE

page 56

Page 56

Page 56